“By April 2020, the city was quiet, empty, and serenely depressing.”

I think someone once asked me, “If you could live in a painting, what would it be?” My answer is and has always been, Nighthawks (1942) by Edward Hopper.

I was first introduced to Hopper back when I was in elementary school. If I remember correctly, we were learning about American Realism, and as a third grader, I had no idea what that meant. Despite my language barrier and lack of art history knowledge as a kid, I was captivated by Hopper’s paintings. I don’t know what it is about his works, but whenever I look at them, I immediately think of American landscape.

Actually, my top favorite artists are all American: Edward Hopper, Wayne Thiebaud, and Grant Wood. I think their works are quintessentially so “American.” People have different perspectives and understanding of “Americanism” when it comes to art, but there is one theme that can only be found in American literature and artworks: isolationism.

During the 19th century, cities were considered unfavorable due to high contamination, pollution, and spread of infectious diseases. The idea of “bad air,” which very much was attached to the rise of industrialization, led to the creation of the Miasma Theory. Before sanitation and waste systems were placed in urban spaces, streets were filled with litter, dead bodies, feces, and disease-carrying animals. Under the lens of science, we know that poor waste management and lack of sanitation cause infectious diseases. However, nineteenth-century society thought that “bad air” caused illnesses and death. Given that medicine was not highly regarded and public health was not yet developed at the time, people came up with unscientific information that shaped American social hierarchy and cultural establishment. Similarly, when the COVID-19 hit the U.S in the spring of 2020, New York City that once was known as a the “greatest city in the world” became the epicenter — an undesirable city. It was during this time when privileged people fled the city — out to the quiet and more spacious parts of the country. By April 2020, the city was quiet, empty, and serenely depressing.

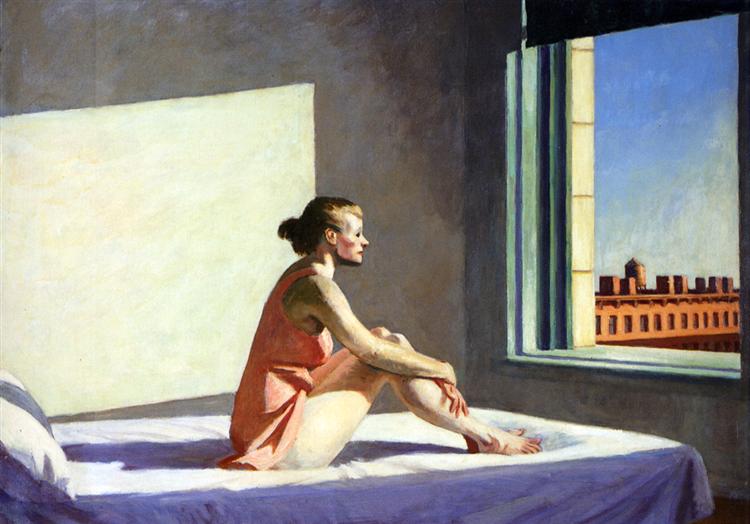

As I saw businesses shut down and people confined in their respective homes — desperately wishing for lockdowns to be over, I kept visualizing Hopper’s Morning Sun (1952). Coincidentally, the New Yorker magazine published an article, Edward Hopper and American Solitude. The author wrote, “Pandemic or not, the artist’s masterly paintings explore conditions of aloneness as proof of belonging.” While I won’t go into the details of what the article discusses, there is one word that I kept attaching myself to. Isolationism.

Perhaps it’s the pandemic living — what has now become the “new normal” — that we’ve adapt to, which very much resemble the themes of Hopper’s artwork. His paintings are mysteriously captivating. With anonymous figures, detailed architecture and buildings, and vacant spaces… it’s almost as if they are scenes from a movie. But it’s these qualities that tie back to aloneness and seclusion that make his paintings American.

Dating back to the 1930s, America’s adoption of isolationism has shaped its political affairs and people’s approach to global issues. Isolationism molded American individualism that is engraved in its culture, politics, and society. Today, I see protestors waving signs that say, “Medical freedom!” or shouting, “My individual rights!” This idea and obsession of individualism have turned extreme to a point in which issues that need collective effort — such as vaccinations and defeating the COVID-19 pandemic— seems out of reach. While we cannot control how one should do or behave, I believe there are consequences followed by actions. Freedom for individualism should not be taken for granted nor misused for toxic ignorance. The American value of individuality and isolationism extends to the arts including Hopper’s cinematic paintings. And because the pandemic has made our lives very much like Hopper’s art, I cannot stop but picture myself in it. Although I doubt that Hopper saw the pandemic coming, it is strangely relatable.

Last month, I took a day trip to Nyack, New York — Edward Hopper’s hometown before he moved and resided in Greenwich Village with his wife. His house sits on top of a hill and right across is the Hudson River. I learned so much about him as an artist and how his upbringing inspired his paintings. He was a loner since he was a child. According to the museum docent, he was bullied by classmates because he was so tall (he grew up to be 6’11 ft). One of Hopper’s quotes was displayed in the house and it wrote, “If you could say it in words there would be no reason to paint.” My interpretation of the quote was that art alone is a language that it doesn’t need words to explain or to tell someone how to perceive it— but rather, it’s a space for artists and audience to imagine. This reminded me of Felix Mendelssohn’s Songs Without Words. In a letter, he wrote, “If you ask me what I had in mind when I wrote it, I would say: just the song as it is. And if I happen to have certain words in mind for one or another of these songs, I would never want to tell them to anyone, because the same words never mean the same things to others.”

Without words, art can carry and tell stories. During this time, I imagine us in a tranquil world where silence is the new luxury. No notification sounds, no vibrations from tech machines, and no headphones attached to our ears — pulling us away from the presence. That is an ideal place that I want to be in, and Cape Cod Evening (1939) lays out this landscape of my current desire in the midst of alarming news about disasters and social media updates. But not every art is inviting for us to imagine. If you learn the meaning behind Salvador Dali’s paintings, you know that his paintings are not meant to be hung in your bedroom for aesthetics. They contain dark surrealism that bleeds disturbing symbols of humanity and of Dali’s mad imagination. Maybe I have this natural tendency to see beauty from where I want to see it rather than respecting the artists by listening to their intentions illustrated in the work. It’s this individual-oriented perception that changes how we go about our lives, interpret things, and let alone exercise our own imagination. Despite Hopper’s mystery and what we may never know about his intentions behind every stroke, for me, his art has become a vehicle to re-imagine our world.

It’s almost September. Season change is around the corner. I work from home. Everyone is trying to survive. As I reflect on the word, “isolationism,” it is not “aloneness” that I think of. Instead, I think of the word, “presence.” In a culture where we have blurred the line between facts and opinions — consumed by alternative facts and virtual reality — we are constantly looking for future-driven answers and constructing answers that we wish to hear. If we could re-imagine a world that is not deviated from reality nor truth and one that enlightens our understanding of what we have become, we may be living through Hopper’s paintings without realizing it. I think his paintings invite us in one solitude.

Leave a comment